CALL US! 1-415-766-2722

Fun@SanFranciscoJeepTours.com

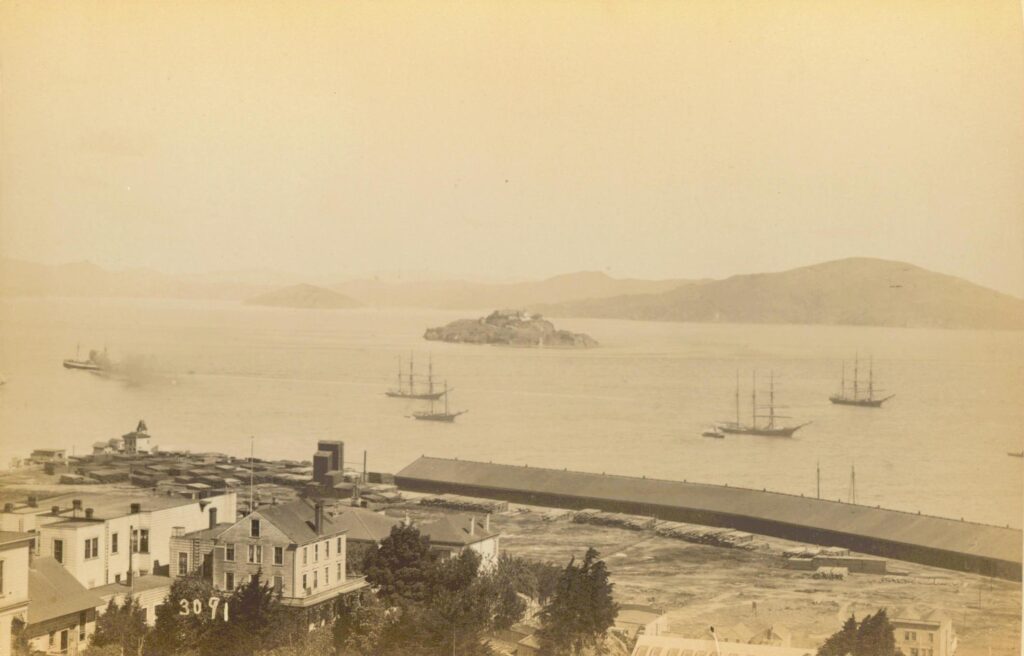

Alcatraz Island is more than a prison. Long before it became The Rock, this windswept outcrop in San Francisco Bay served as a navigational landmark, military fortress, military and federal prison, a powerful stage for Native American protest, and eventually one of the most visited historic sites in the United States.

This page is your definitive, story-first timeline—with the key dates, the “why it mattered,” and the details people always wonder about (escapes, famous inmates, the lighthouse, the occupation, and the myths Hollywood made famous).

The recorded story of Alcatraz begins in 1775 when Spanish naval officer Juan Manuel de Ayala became the first European to sail into what is now San Francisco Bay. His expedition mapped the bay and named an island La Isla de los Alcatraces.

The name was later Anglicized to Alcatraz. While the exact translation is debated, alcatraces is most commonly defined as meaning “pelican” or “strange seabird.” Either way, the earliest identity of Alcatraz wasn’t “prison.” It was “bird island.”

In 1848, California became U.S. property at the end of the Mexican–American War—right as gold was discovered along the American River. San Francisco’s population and importance exploded, and the U.S. Army moved quickly to protect the bay.

In 1850, a joint Army and Navy commission recommended a defensive network to guard San Francisco Bay. President Millard Fillmore signed an executive order reserving land around the bay—including Alcatraz—for “public purposes.”

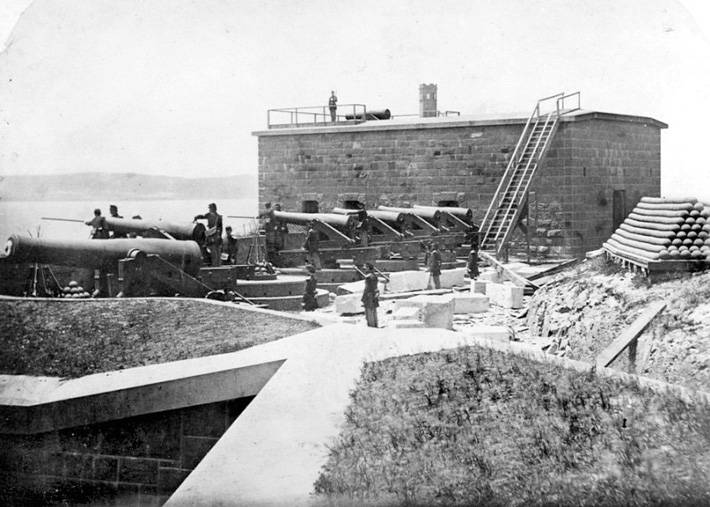

Alcatraz was planned as part of a defensive triangle with Fort Point and Lime Point, intended to protect the entrance to the bay. The Army made plans to install more than 100 cannons, making Alcatraz the most heavily fortified military site on the West Coast.

Here’s the twist: despite all that preparation, Alcatraz never fired its guns in battle. But its next role would last far longer than the fortress era ever did.

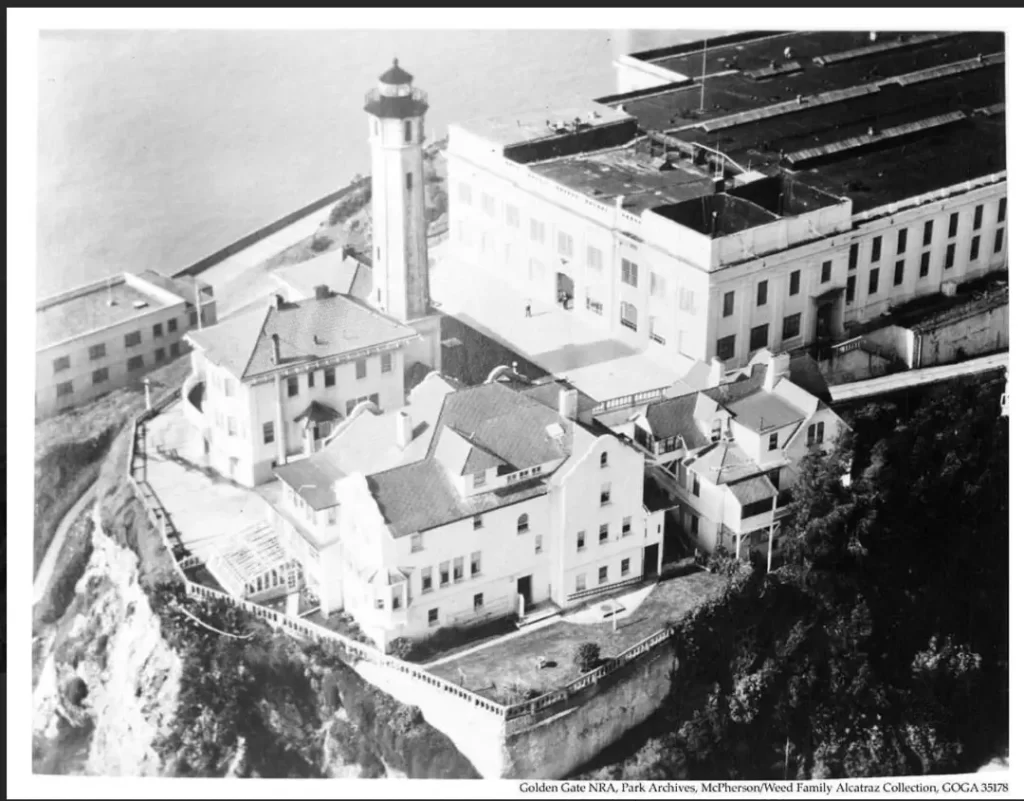

In 1854, the Alcatraz lighthouse began service as the first operational lighthouse on the Pacific Coast. Before Alcatraz became famous for incarceration, it was known for guidance—helping ships navigate safely into San Francisco Bay.

In 1859, Capt. Joseph Stewart and 86 men of Company H, Third U.S. Artillery took command of Alcatraz. As the Civil War began in 1861, Alcatraz’s military importance increased—and so did its use as a detention site.

By the early 1900s, Alcatraz’s fortress identity had faded—but its prison identity had fully taken hold.

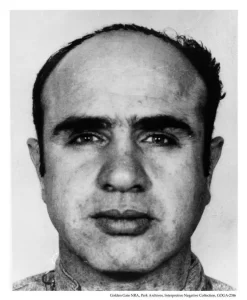

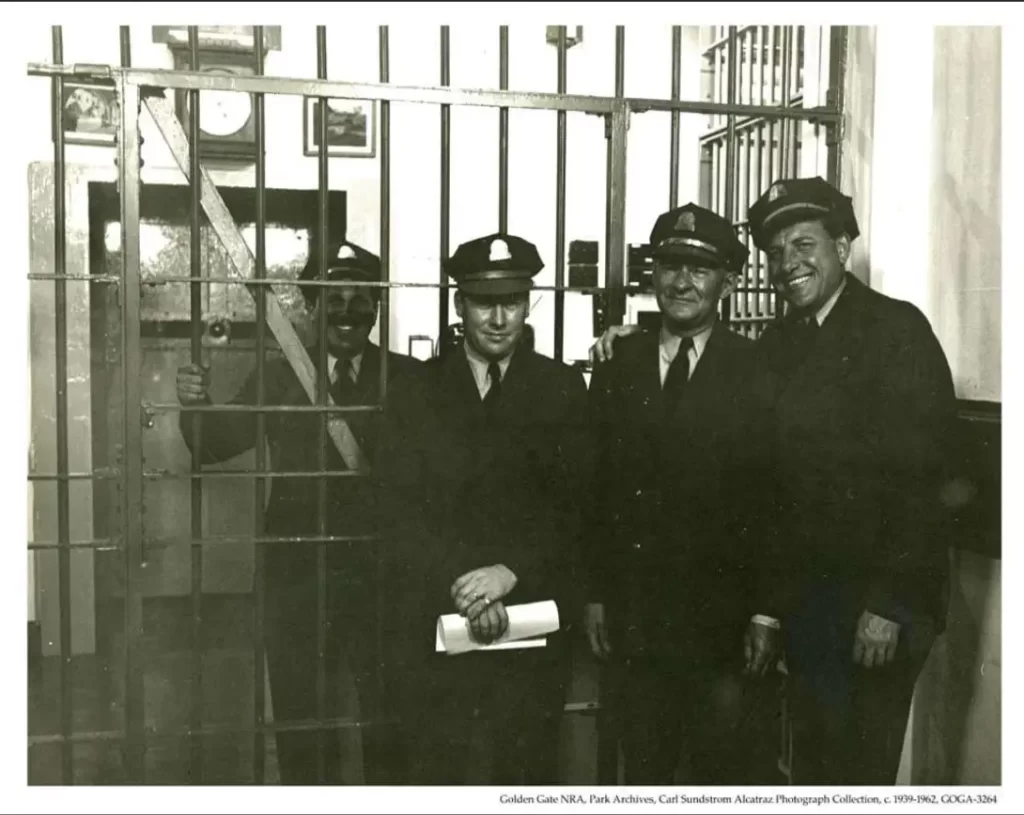

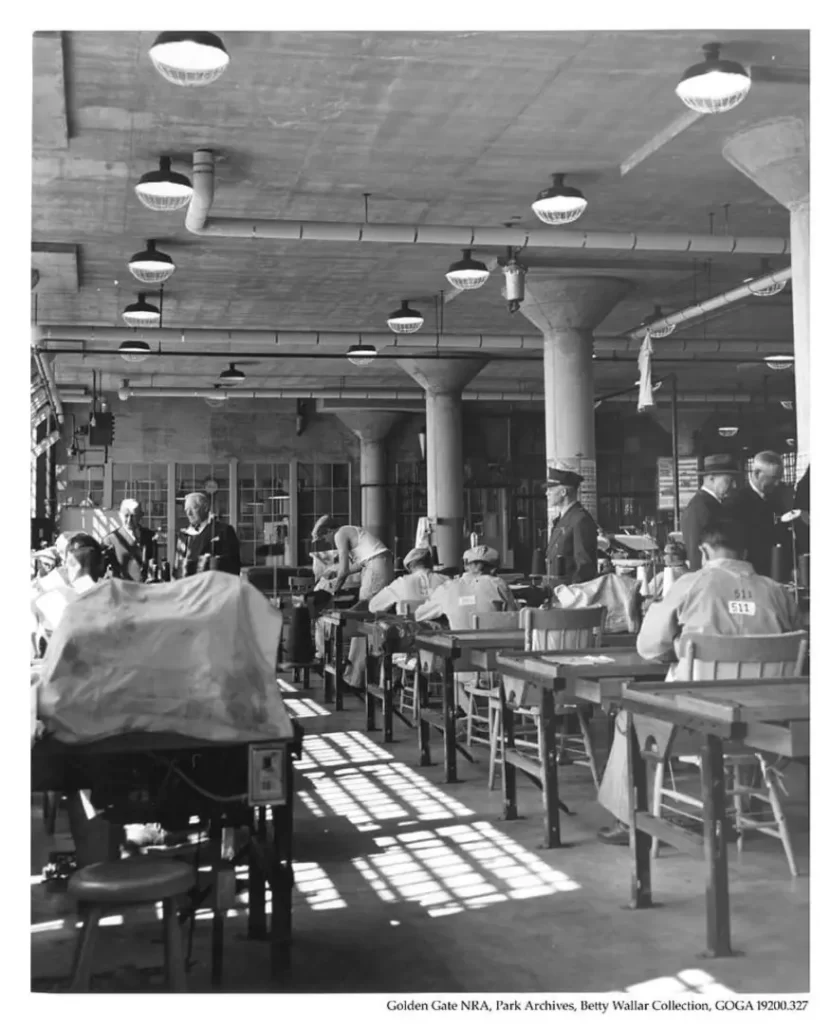

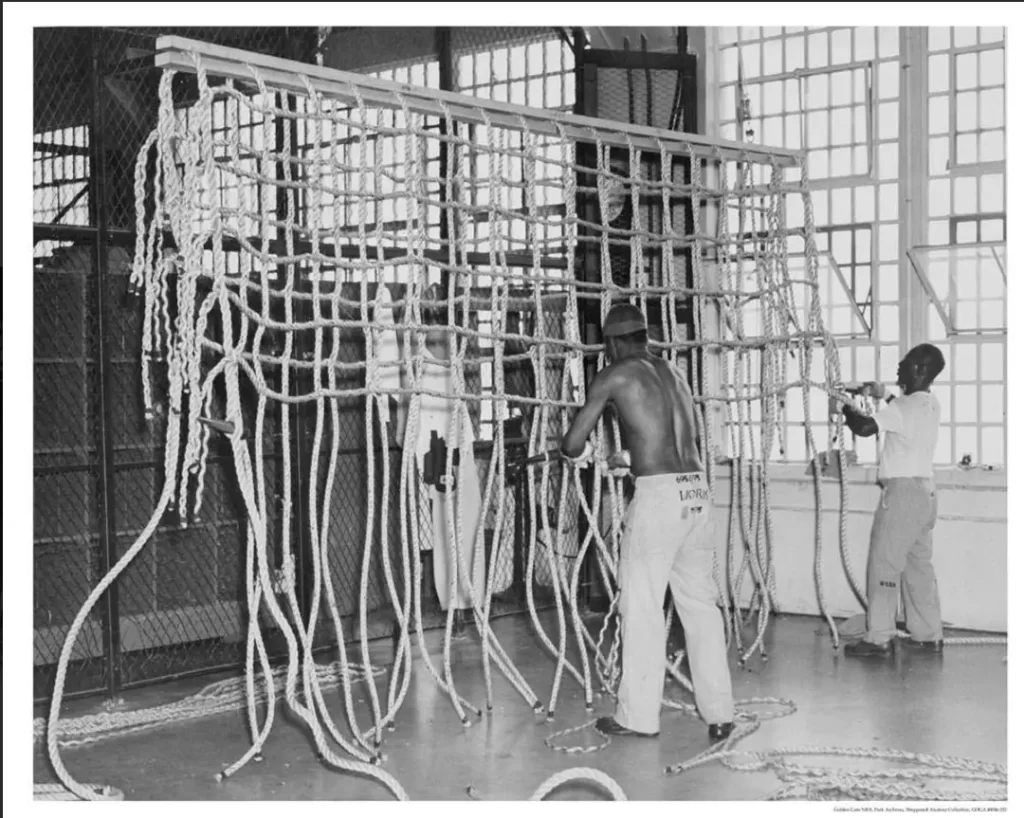

In 1934, Alcatraz was transformed into the most secure federal penitentiary in the United States—designed for inmates considered violent, dangerous, disruptive, or escape risks. The federal government wanted a maximum-security, minimum-privilege prison that would set a tone: the rules matter.

While famous names existed, most prisoners were not celebrity criminals. Many were inmates who refused to conform in other federal institutions or were considered serious escape risks.

Fun reality-check: Stroud never kept birds at Alcatraz. His bird studies happened earlier at Leavenworth. At Alcatraz, he spent years in segregation and later the prison hospital before being transferred off-island.

Cells in B & C Block averaged about 5 feet by 9 feet—with a sink (cold water), toilet, and a small cot. Many inmates could extend their arms and touch both walls.

There were 336 cells in B & C Block. (Some records note there were originally 348, with 12 removed when stairways were installed.) D Block included segregation and confinement spaces: 36 segregation cells and 6 solitary confinement chambers.

Yes. Inmates could receive one visit per month if approved directly by the Warden. No physical contact was allowed, and conversations were monitored. Inappropriate conduct could mean losing visit privileges.

Alcatraz wasn’t only inmates and officers. At any time, roughly 300 civilians (including women and children) lived on the island in staff housing. Families had a small store and even a bowling alley, and they shopped on the mainland using frequent scheduled boat runs.

Surprisingly, yes. Some inmates reported that having your own cell was a major improvement over other prisons, and several said food quality was among the best in the federal system. That doesn’t make Alcatraz “pleasant”—but it helps explain why its reputation is more complex than movies suggest.

No. Alcatraz had no capital punishment facilities. Prisoners sentenced to death were transferred to state institutions such as San Quentin for execution.

Between 1934 and 1963, there were 14 escape attempts involving 36 men (two tried twice). Outcomes included capture, deaths by gunfire, drownings, and several “missing and presumed drowned.”

Officially, no one ever successfully escaped Alcatraz. But the definition of “successful” is the controversy: is it getting off the island, reaching shore, or reaching shore and never being caught?

A popular myth is that “sharks made escape impossible.” In reality, there are no man-eating sharks in San Francisco Bay. The true threats were:

It is possible to swim from Alcatraz under the right conditions—strong swimmers have proven it. But for prisoners without training, tide knowledge, and preparation, the odds were slim.

The most famous attempt involved Frank Morris and brothers John and Clarence Anglin. Their disappearance remains one of the great American mysteries—and the reason Alcatraz’s escape mythology refuses to die.

Alcatraz didn’t close because of the Morris/Anglin escape story. It closed because it was too expensive and the infrastructure was deteriorating.

The island’s isolation—its greatest security feature—was also its biggest cost driver. Everything had to be shipped by boat: food, fuel, supplies, and even fresh water. Estimates suggested millions were needed for restoration and maintenance, not counting daily operations. In 1959, Alcatraz was reportedly nearly three times more expensive per inmate than other federal prisons.

On March 21, 1963, USP Alcatraz officially shut down.

After the prison closed, Alcatraz sat largely unused—until it became the site of one of the most significant Indigenous rights actions in modern U.S. history.

On November 20, 1969, Native American activists associated with Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz, citing broken treaties and demanding that unused federal land be returned to Indigenous people.

The occupation lasted 19 months and became a watershed moment in Native American activism. Some of the graffiti from this era remains visible today as a powerful reminder of the island’s layered history.

In 1972, Congress created the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and Alcatraz Island became part of this National Park Service unit. The island opened to the public in 1973.

Today, Alcatraz is:

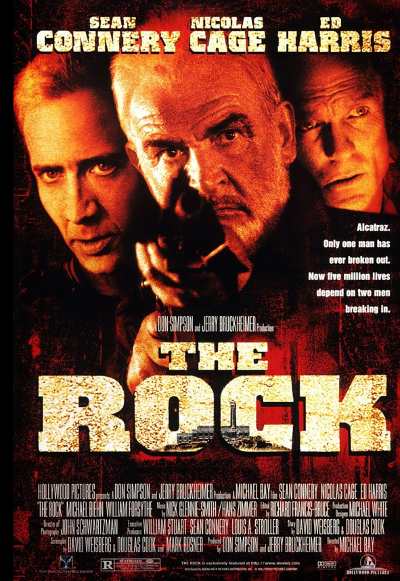

Alcatraz is a real place with real history—but Hollywood poured gasoline on its mystique.

The 1979 Clint Eastwood film Escape from Alcatraz made the 1962 escape attempt a permanent part of pop culture. Other must-see films that mix Alcatraz history with fiction include:

If you’re the kind of traveler who loves visiting places you’ve seen on screen, Alcatraz is basically an all-time great.

For the full deep dive, this companion guide is made for you: 21 Movies and 14 TV Shows That Explored Alcatraz (“The Rock”).

The name traces back to 1775 when Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala mapped San Francisco Bay and used the term alcatraces. It’s commonly interpreted as meaning “pelicans” or “strange seabirds,” and the word later Anglicized to “Alcatraz.”

No. Alcatraz began as a named island and navigational landmark, then became part of a coastal defense system, then a military prison, and only later a federal penitentiary (1934–1963). After that, it became a major protest site and later a National Park.

In the 1850s, the U.S. Army fortified Alcatraz as part of defenses protecting the bay. It was planned as a major cannon site and became one of the most heavily fortified West Coast military locations—though it never fired its guns in battle.

Alcatraz became a federal penitentiary in 1934 after being transferred to the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1933.

Well-known inmates included Al Capone, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, Alvin Karpis, and Robert Stroud (the “Birdman of Alcatraz”). Most inmates, however, were not famous—they were considered high-risk or disruptive within the federal prison system.

There were 14 escape attempts involving 36 men during the federal prison era (1934–1963). Officially, no escapes are confirmed as successful, though debate continues—especially about the 1962 Morris/Anglin attempt.

Officially, no one is confirmed to have escaped. Several inmates are listed as “missing and presumed drowned,” and the definition of “successful escape” (off the island vs. to shore vs. never caught) keeps the debate alive.

It closed primarily due to cost and deteriorating infrastructure. Alcatraz was expensive to operate because everything had to be shipped by boat (including fresh water), and major restoration was needed. It did not close because of escape attempts.

Beginning on November 20, 1969, Native American activists associated with Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz for 19 months to protest federal policy and broken treaties, and to call for Indigenous cultural and educational facilities. The occupation became a landmark moment in modern Native American activism.

Alcatraz is a National Park site within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, operated by the National Park Service. It’s a historic site, museum, and wildlife habitat visited by over a million people each year.

Want to go beyond the timeline? These companion reads expand the story and help you dig deeper:

Alcatraz Island is unforgettable—but pairing it with a guided city experience makes the day smoother, richer, and way more relaxed. Instead of juggling routes, parking, and ferry logistics, you can explore San Francisco’s top neighborhoods and viewpoints before heading out to The Rock.

Our Alcatraz Ferry and San Francisco Private City Tour combines two experiences travelers usually book separately into one well-timed plan:

It’s the easiest way to understand San Francisco before you step inside its most famous island—without rushing, backtracking, or missing the good stuff. Explore the Alcatraz + San Francisco City Tour Combo

Pro tip: Alcatraz tickets often sell out weeks in advance. Booking the combo locks in your ferry access and your city sightseeing in one move.

Alcatraz pairs best with waterfront icons and quick scenic stops near the Embarcadero—easy to stack before or after ferry time.